Environmental scientists at ANSTO have been undertaking research to gain a better understanding of the potential impact of contaminants on decommissioned offshore oil and gas infrastructure since 2017.

The research will help inform whether all decommissioned infrastructure needs to be completely removed (as the legislation currently stands).

A scale may form within subsea pipes during operation, much like cholesterol on the inside of arteries. These scales may contain naturally occurring radioactive materials (NORMs) as contaminants.

There is currently a knowledge gap on the potential impact of these contaminants on the marine ecosystem as industry and regulators try to assess if some assets may be left in place.

Some research has suggested the subsea infrastructure may be beneficial and act as an artificial reef.

Algae, oysters, coral and other invertebrates colonise the pipelines during operations and will likely exist for many years after operations cease if the pipe is left on the seabed.

A recent experiment in the aquatic labs (part of the Vivarium facility) at ANSTO was carried out to gain baseline information on the effects of exposure of naturally occurring radioactivity on marine algae, that are usually the first marine organisms to take up residence on the outside of pipelines.

Dr Tom Cresswell, who is leading the research for ANSTO, said that PhD candidate Amy MacIntosh (pictured below) had set up a unique experiment with a sealed radioactive source in ANSTO specialist laboratories.

The source was placed at different distances from the algae for 72 hours.

“This period is equivalent to chronic exposure that you expect in the undersea environment. We are assessing if there is any impact on growth rates and the ability of the algae to photosynthesise UV light for energy.”

“We use a variety of techniques in environmental toxicology, radioecology, radiochemistry and materials science and access a suite of nuclear and accelerator facilities for a holistic understanding of the fate of key contaminants that may be present in pipeline scales,” explained Dr Cresswell.

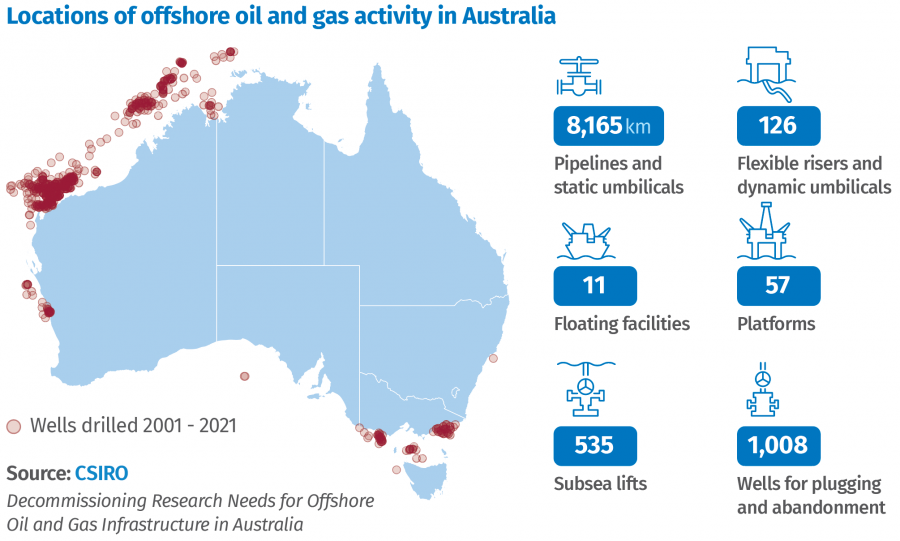

Locations of offshore oil and gas activity in Australia;

- 8,165km of pipelines and static umbilicals

- 126 flexible risers and dynamic umbilicals

- 11 floating facilities

- 57 platforms

- 535 subsea lifts

- 1,008 wells for plugging and abandonment

The goal is to minimise decommissioning costs, which have been estimated at $60 billion for more than 65 offshore installations scheduled for decommissioning in the next 30 years, while ensuring the highest levels of environmental protection.

In previous work, ANSTO scientists measured the levels of NORM contaminants in pipe scale and developed a model of potential radioactivity dose to biota.

Laboratory organism exposures associated with this work suggested the impacts might be negligible.

Gathering more data will be important in informing risk assessments during decommissioning planning.

ANSTO has considerable expertise in monitoring both natural and anthropogenic radioactivity in the environment as well as field experience.

Mercury has also been detected in pigging dust collected at the end of a subsea gas pipeline.

A comprehensive assessment determined the amount of mercury concentration, its chemical forms and potential for interactions with marine organisms. Investigations were supported by the production of mercury radioisotope tracers in the OPAL multi-purpose reactor.

The chemical form of mercury, which directly impacts its mobility and potential uptake by marine organisms was determined using the X-ray absorption spectroscopy beamline at the Australian Synchrotron. Controlled laboratory tests conducted at Lucas Heights suggested the form of mercury was inert and not readily taken up by marine organisms.

ANSTO is involved in an International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Working Group on NORM remediation from the oil and gas industry and is collaborating with European researchers and regulators on offshore infrastructure in the North and Norwegian Seas.